Sega Master System FM Mod

About 60 Sega Master System games include music data for Frequency Modulation (FM) synthesis. Yamaha’s YM2413 (or OPLL) sound chip, employing only 2 operators, was a cheap alternative to the FM synth chips found in its flagship DX7 keyboards and frequently employed in advanced arcade cabinets. Sega’s Mark III console, released only in Japan, could play the FM data when an external sound unit accessory was connected, and, later, the Japanese version of the Master System included the YM2413 chip in the internal circuitry. Unfortunately, the North American and European releases of the Sega Master System were not built to support the expanded audio, even though most game cartridges retained the FM sound data.

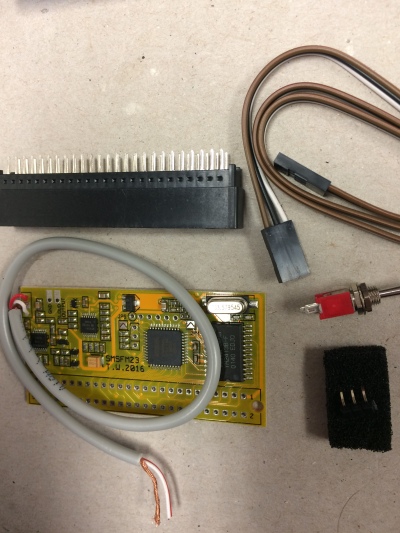

I recently modded two North American Sega Master System consoles to read and perform the FM sound data, using a PCB with the YM2413 chip that was built and designed by Tim Worthington. These mod and kits are explained on this website. Although diagrams and schematics are posted online, I have not found a detailed, step-by-step guide; therefore, I am blogging my experience with installing two kits for those, like me, who may need more guidance. I am not an electrical engineer by any means, so please comment below if you have any suggestions for improvement. My approach worked well for my two consoles, but please be aware that differences exist in the variant releases of the Sega Master System.

EDT’s video proved an invaluable resource to my approach.

SUPPLIES (Required)

-Tim Worthington’s FM Sound Kit (available for purchase here).

-Phillips head screwdriver

-Soldering iron

-Solder and flux

-Drill with 5/16 bit

-Small gauge wire cutters

SUPPLIES (recommended)

-Electrical tape

-Desoldering pump or wick

-Shears/Tin snips

-Jeweler’s flathead screwdriver

-91% Isopropyl Alcohol

-Cotton swabs

PART 1: Preparing the PCB

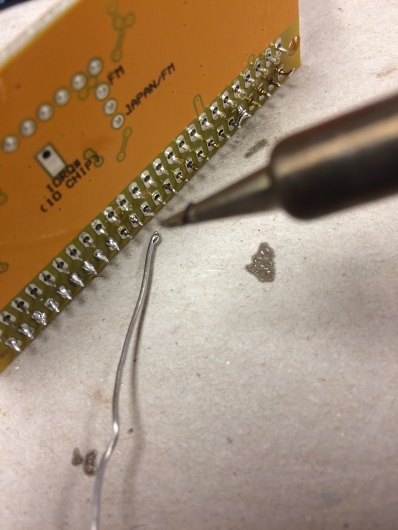

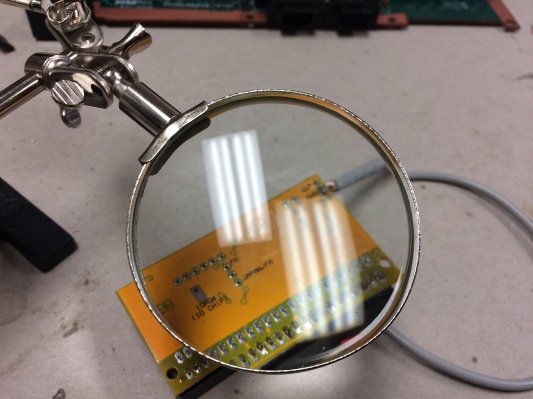

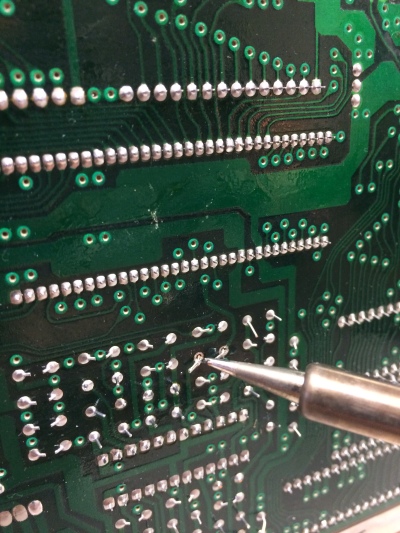

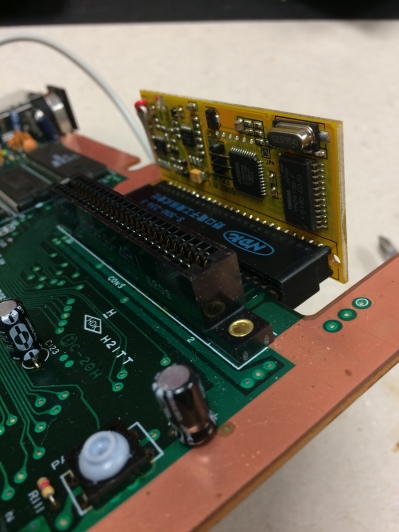

-Slide the pin connector through the holes in the PCB and solder each pin on the rear side. To ensure perpendicular alignment, use something to prop up the board so the two rows of pins are even. Careful not to bridge adjacent pins (see picture); use a desoldering pump or wick to remove any excess solder.

-Slide in the toggle pin connector so that the long end runs parallel to the front of the PCB. Then solder the 3 short end pins on the rear of the board (where the text FM and Japan FM is printed.

-You’ll see that the plug on the provided wire for the toggle switch will slide right onto the 3 pins that are running parallel to the front of the PCB.

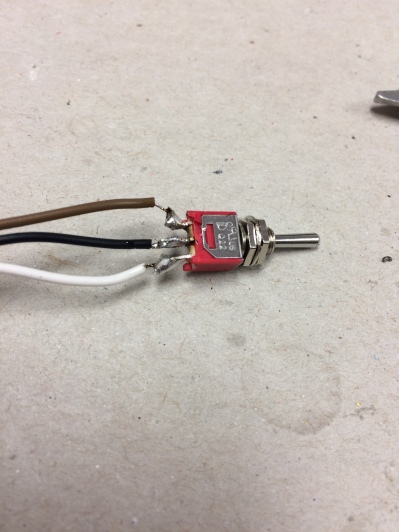

Part 2: Preparing the Toggle Switch

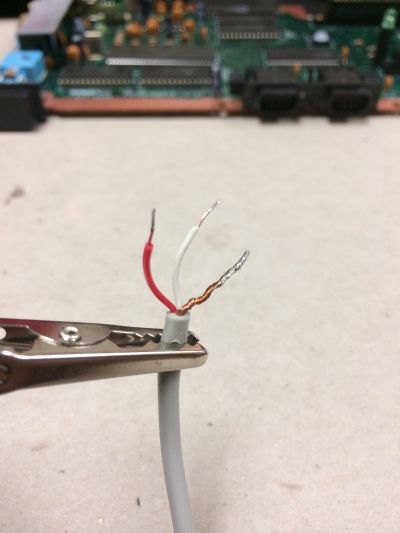

-While the plugs on the wire provided with the kit fit snuggly on the pins for the PCB, I found that they were too small for the terminals on the toggle switch.

-Therefore, I cut off the plug on one end, stripped the 3 wires, and then threaded through and soldered to the 3 terminals, being careful not to bridge any of the three wires with solder on the back of the toggle switch.

-Note: Keep the plug on the other side of the wire, as it will slide easily onto the PCB pins.

Part 3: Preparing the SMS Console

Disassembly. This video may be helpful.

-Remove the six screws on the rear of the console case with the Phillips screwdriver and pull apart. Put screws and console top aside.

-Then remove the 5 screws around the base of the RF shield as well as the screw on top of the RF shield. NOTE: the screw on top of the RF shield is different and includes a washer.

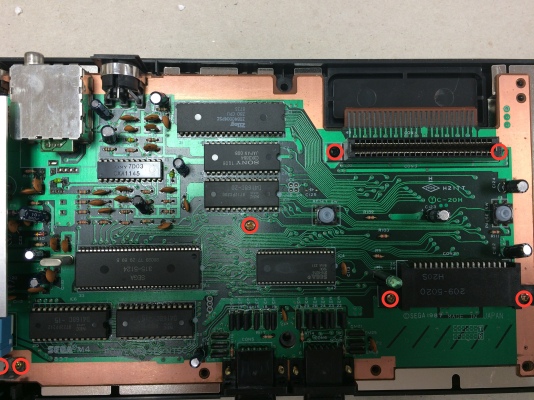

-Finally, remove 7 additional screws that hold the motherboard in place. See the diagram pictured below (one of the two screws on the bottom left is slightly cut out of the photo).

-You can now remove the motherboard.

Wiring SMS motherboard

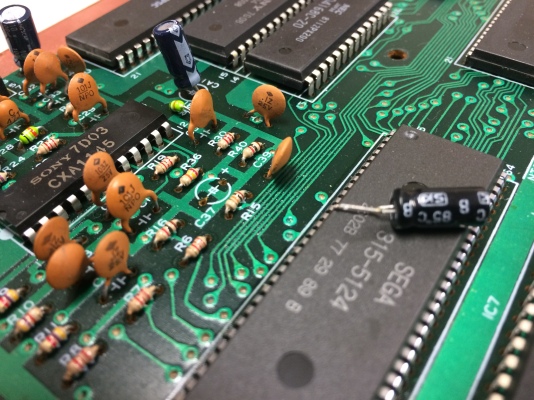

-Remove the electrolytic capacitor at C37 by locating the traces on the rear, warming the existing solder with you iron, and pulling the capacitor away from the other side when the solder is molten.

-Locate ground plane to the left of the same capacitor field and scratch away the green coating with a jeweler’s flathead screwdriver.

-Prepare the wire provided by stripping the sleeves to reach the target locations on the motherboard and then tin the ends.

-Thread the red and white wires though the positive (+) and negative (-) polarities at C37, and solder the traces on the rear of the motherboard. NOTE: The image provided on the website above has the red and white wire locations reversed. The white wire should be on the right (+ve), and the red wire on the left (-ve).

-Apply flux to the ground plane you just scraped on the component side and solder the threaded copper wire to it. Once completed, wrap electrical tape around exposed wire threads to keep them from reacting to nearby components.

Part 4. Final assembly.

-Clean the pins on the expansion port with some alcohol and cotton swabs.

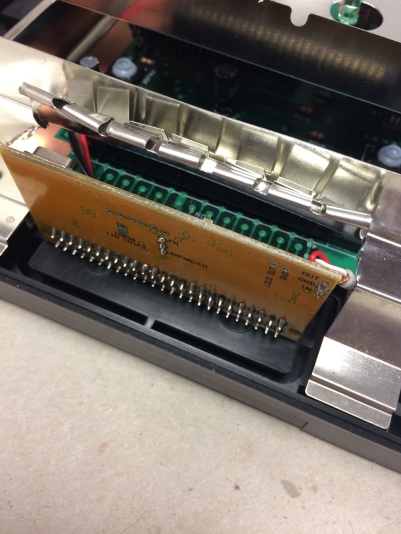

-Slide the pin connector on the PCB onto the expansion port pins. It should slide all the way in tightly.

-Attach the motherboard to the bottom casing with the 7 screws left to the side.

-Use shears or tin snips to cut the RF shield and roll the fingers up so the FM sound board will clear without making contact with the shield.

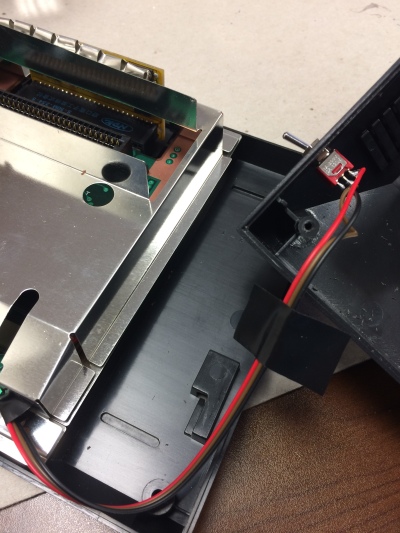

-Attach the plug on the toggle switch wire to the PCB (if you haven’t already) and put the RF shield back into place with the 5 screws left aside, as well as the smaller one for the top of the shield that has a washer.

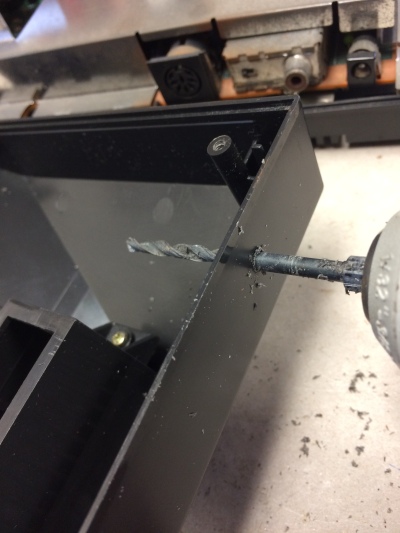

-Use a 5/16 bit and drill a small hole through the lid of the console in the desired location. I used the rear left side, so it would have the same clearance as the power and AV cables wherever I set up my SMS.

-Make sure the hole is just wide enough to slide the threaded part of the toggle switch through and fasten with the included washer and nut. Electrical tape can be used to hold the wire in place, so it will not block access to the cartridge and card slots.

-Carefully place the console lid into position, making sure that the toggle switch wire doesn’t get pinched. (Note: I took photos during both console mods, so pay no attention that the toggle switch wire colors are different at times).

-Put the 6 outer casing screws back in. Done!

Optional. Label the toggle switch. The direction will depend on how the wires were connected to the pins with the plug on the PCB.

Once assembled, you should be able to boot the FM sound data from the Sega Master System cartridges that have it (they are listed at the website above). Some games will require you to use the Japan FM setting on the toggle switch. Other games will require a patch or ROM from a flash cart like the Master Everdrive. You cannot toggle during gameplay, as the FM data is only loaded at boot up.

Many thanks to Tim Worthington for an outstanding mod and kit!!!

Please leave comments below if you have any questions or any suggestions for improvement. I hope this step-by-step guide will be helpful! =)

My Experience Publishing with Hybrid Pedagogy

I had the privilege to publish a short-form article with Hybrid Pedagogy this summer. It was a collaborative process through and through. The essay was co-authored with my colleague, Jessica Mahoney, and the peer-review process was completely open, allowing me to directly converse with the journal’s editors as Jessica and I made revisions.

As scholarship adapts to changes in technology and information sharing in the digital age, I see tremendous benefits in this sort of peer review. The time lags that occur in the traditional format may be suited to longer, more in depth writing, but research aimed at keeping up with the rapid exchange of ideas will need a more instantaneous platform. Although I doubt traditional scholarship will completely die out–it does offer something of tremendous value–I suspect the acceptance and quality of short form writing and open peer review will continue to grow.

Furthermore, I believe this is a great model for student writing. The systematic routine of leading students through the motions of 5-part expository essays may have little relevance for their writing in the future. Students should write to learn to think and communicate both valid and compelling ideas. Co-authorship and open peer review may be the way to increase motivation and participation.

Thoughts on Commission on the Humanities and Social Sciences

The big news of last week was the recommendations made in the report of the Commission on the Humanities and Social Sciences for more support for and emphasis on teaching those disciplines. Administrators and faculty alike have begun a series of back-patting as media ranging from mainstream news outlets to the Chronicle have quickly celebrated validation for continuing to promote traditional fields of study.

The report’s presentation on the national level, though, leaves a lot of questions as to the implications for the majority of Americans in local school districts and state institutions of higher education. Will the optimistic news have any significant impact on changing public sentiment toward the value of a college degree? Will local and state governments suddenly begin investing more in “big picture” disciplines? Will humanities and social science researchers try to reach mainstream issues and audiences?

The announcement reminds me of the championing of liberal arts degrees by employers, proclaiming that they seek talented, well-rounded employees who can adapt to change, communicate effectively in writing, and think critically. This is all good, but what impact do these candid statements have on actually hiring trends? Most college graduates will submit their first job applications to mid-level hiring managers and receive the scrutiny of automated screening programs. Job descriptions match position titles with the ever-growing selection of career-minded majors that reference specific jobs rather than timeless liberal arts. It seems to me that companies ought to invest as heavily in humanities-based grants as they do STEM ones if these qualities are needed in the workforce.

Where does this leave teachers? It would be a difficult battle to advise undergraduates to go against the post-recession culture of career-sensitive education. But that does not mean that traditional liberal arts, humanities, and social sciences are mere buzzwords. Persistent reflection on the broad skills, global perspective, and interdisciplinary mindset these fields cultivate should be at the forefront of every class. College faculty in these areas need to expose ALL students to the relevance of traditional subjects in contemporary contexts. This includes courses for both majors and non majors. And these qualities and skills are not inherently tied to traditional content. Emphasis on writing, creativity, and problem solving should be recurring functions of all classes. It’s up to teachers to guide students through process of understanding the value of the humanities, whether new students continue to choose modern professional degree programs over traditional fields of study.

The report encourages institutions to support teachers in these disciplines. If students trend away from these majors, administrators will need to rally behind their effective teachers. It may be difficult to sustain departments anchored by senior research scholars and their graduate students as the number of undergraduate majors continue to decline. In agreement with the report’s criticism of inward-focused trends, emphasis should be placed on making these fields relevant to the general studies curriculum by addressing contemporary needs in local, national, and global contexts. Courses of this nature should focus on collaborative, interdisciplinary problem solving and model the application of humanities and social sciences to issues in need of real scrutiny and change. Content will be the byproduct, not the focus.

When to break it to ’em

I’ve addressed “why you need this course” many times in my syllabi and first day spiels. The intention to “get the record straight” before the class commences is certainly understandable. We don’t want students to harbor skepticism that may inhibit their learning experience. Furthermore, we may also wish to prevent any undesirable comments on course evaluations and www.ratemyprofessor.com. We want the buy in immediately, so we turn to the selling mode on day one.

With this approach, however, the professor potentially risks one of the most important outcomes of higher education: critical thinking. Indoctrinating students before they have had an opportunity to engage with the material is denying them an environment where they can challenge the system. Do you want your students to speak their mind in class? Do you want students to develop thesis statements that creatively go against the majority? Do you want students to deconstruct long-standing theories? Of course you do!!! Well, then let them.

You cannot have is both ways. If you present students with your offer of value on the first day, then they will make their decision on whether to buy into it on the first day. Either they will accept the value because you told them to or they will tune out because your actions told them that you’re a phony. The semester will be a drag. However, if you want them to critically engage with course topics, you have to let them call you out from time to time. This is what an intellectual community does.

Breaking the news to them that your course will have long-term value is something that should come later in the semester and it should be initiated by the students. Everything will need to be thrown on the table when students begin to challenge what you’re doing and to question whether it’s worth their time. Your willingness to put your plan on hold when the time presents itself will convince students of your authenticity as an educator. Furthermore, all sides are now privy to course content and thus in a better position to discuss on equal grounds. It’s not fair to tell students they need the content of the course when you haven’t even shown it to them yet. If you can guide the discussion to allow students to formulate plausible connections between their learning experiences and future scenarios, the buy in will be far greater. And they will have arrived at this by exercising the inquisitive mindset we are trying to cultivate.

Not every student will see the connection, even after this conversation. It will be tempting to consider it shortsighted. However, if the class has the opportunity to challenge you and the encouragement to support that challenge with evidence, then they’re modeling something more valuable than you could over sell them with a lecture.

Defining the Liberal Arts in the 21st Century

One of the challenges liberal arts institutions face is defining liberal arts for prospective students and their parents. Although the curriculum and its benefits seem obvious to faculty and administrators, it can be a tough sell from time to time. This is especially true today amidst growing skepticism about the value of higher education and a strong desire for job-specific training. The term liberal arts has complicated usage because it is defined differently, depending on the context. Over the years I’ve begun framing the concept of liberal arts from five perspectives.

1. The Traditional Subjects. The Trivium (Logic, Rhetoric, Grammar) and Quadrivium (Arithmetic, Geometry, Music, and Astronomy) of the Middle Ages–which you can see displayed in the banner of this website. These seven areas defined the structure of higher education in Medieval Europe and are an important model for the general education curricula found in primary and secondary schools as well as the core requirements of most four-year, bachelor of arts degree programs.

2. General Education Requirements. Most college and university undergraduate degree programs now require a standard set of courses or subject requirements outside of the major area. Depending on the type of institution (private liberal arts college, public university, etc.) and the type of degree (bachelor of science, bachelor of arts, etc.) the number of courses and proficiencies may vary. The most common requirement areas include composition, speech, literature, natural sciences, social sciences, fine arts, foreign language, intercultural, quantitative, and physical education. This list is simplified, since the requirements could have slightly different names, definitions, or sub fields that satisfy them. Most students equate liberal arts to this framework, because it is clearly itemized for them on degree requirement checklists. The challenge is showing students that these course requirements are established to ensure the breadth of knowledge, experience, and exposure rooted in a liberal arts education.

3. High Impact Experiences. Some components of the curriculum are not defined by a particular course or field of study, but rather an experience that should dramatically impact the student and significantly further their development and preparation for life after graduation. Some of these experiences include internships, capstone projects, service learning, comprehensive exams, a thesis, and study abroad, although other types of experiences could also be added to this common list. Sometimes these components are specific requirements to be filled and other times they are unique opportunities the institution provides for students that may set the institution apart from competitors.

4. Skills for Successful Careers. In other contexts the liberal arts are defined by a set of skills a student will develop that will help them thrive in the workforce, no matter their major (i.e., transferable). The courses and experiences of the liberal arts education are designed to challenge students in these areas so they are prepared to compete in the global economy. These skills include oral and written communication, cross-cultural sensitivity and awareness, research and information literacy, analytical thinking, creativity, synthesis, problem solving, and critical thinking, among others. Often these are skills itemized on job descriptions. Showing students how courses engage in skill development and that these skills are what employers desire will help broaden the discussion of the benefits of a liberal arts education.

5. Higher Purpose. The final framework for defining the liberal arts serves the institution’s higher purpose, usually expressed in the mission statement. I like to think of this list as desirable ways of describing alumni, no matter what direction they take post graduation. This list would include moral character, leadership, civic engagement, global citizenship, life long learning, among other things. Although the curriculum cannot define attributes as an outcome of specific courses and experiences, the nature of liberal arts study should ideally cultivate these traits in students.

It’s difficult to package the nature of the liberal arts into a brief sound bite or slogan. As institutions continue to adapt to changing public attitudes toward higher education, it will be important to remember the contexts in which the term “liberal arts” appears. One can define the liberal arts from a variety of angles. When explaining the value of a liberal arts education, it will be important to be aware of how the term is used and received in conversation.

The 5-Point Forum Post

One of the most commonly used components of online course management sites is the discussion forum. Many instructors require students to post reflections on assigned readings with the ultimate goal that an intellectual dialogue will materialize in the forum. I’ve experimented with this approach for several years now and have developed a 5-point grading rubric that has yielded more insightful student writing and has improved assessment efficiency:

A “5” Response follows directions and is well organized, clear in prose, and original in thought. The submission is highly polished and free of grammatical and spelling errors. The author references supporting resources properly, makes clever use of analysis and course terminology, and demonstrates a high level of critical thinking and persuasive writing. Excellent.

A “4” Response follows directions, presents good organization and clear prose, and provides some original ideas. There may be a misspelling or grammatical error, but the submission is acceptable in writing style. The author refers to appropriate resources and provides some discussion of the piece, event, or essay. The author may occasionally get off topic and include some ideas that do not strengthen the submission. An original thesis is present, but the argument may be lost at times. Good.

A “3” Response has some recognizable organization and readable prose, but summarizes rather than argues. There are large block quotes or paraphrased passages from the assigned reading that are not effectively integrated into the argument. There are frequent misspelled words and grammatical errors and the formatting does not always follow directions. A musical piece is discussed, but not tied into the argument, and there is little evidence of critical thinking. Average.

A “2” Response rarely follows directions. The topic is related to the assignment but there is no argument that responds to the prompt. There is no reference to the provided resources or poor use of them. The submission is rife with grammatical and spelling errors. It appears that the student has cut and pasted information from various sources and strung the ideas together into an incoherent mess. Components are missing, such as a discussion of the required piece, event, or essay. Poor.

A “1” Response is incomplete. The word count may be well under the requirement and the author has clearly not read the directions and taken interest in the assignment. The writing style is incomprehensible at times and the focus is unclear. The student has submitted a related, but off topic writing sample for this assignment. Failing.

A “0” Response is absent or plagiarized.

For this system to work, students must have a clear understanding of what “critical thinking” means and be able to recognize the difference between quality and poor college writing. In my experience, students will submit their best efforts once they have actively explored a range of samples I provide them. I give the students 2 or 3 anonymous posts from previous semesters along with the rubrics. Groups evaluate the examples and assign grades using the 5-point scale. I ask each group to report their grades and explain why one submission demonstrates critical thinking and another does not. The concensus is usually that critical thinking requires the author to present an original idea and support it with examples from both within and outside of the assigned reading. The rubrics are helpful, but the followup assessment and discussion are what really encourage the best student writing for the semester.

Online course management discussion forums are a useful tool for engaging students outside of class with a discussion of major course topics. However, it is not enough to grade students on their “participation.” The public forum is a fruitful opportunity to push students to put their best work forward and to adopt critical thinking habits for the semester. The 5-point rubric offers students clear expectations for quality work and gives instructors an efficient evaluation tool.